Welcome to this new course of the Complete Guide to Business Management. Here we go learn the notions of Working capital (WC) and working capital requirement (WCR), beginner level, with the aim of introducing us to the inner workings of general accounting and business management.

This content is part of the course “Business Management for Entrepreneurs: A Complete Course to Better Manage Your Business” find it on Tulipemedia.com 💰📈

We learned in the previous chapter what did a balance sheet consist of. Here, we will use this famous assessment in order to discover two very important notions to understand in corporate finance : THE working capital, and the working capital requirement.

These are terms that bankers, financiers, and accountants understand very well, and as decision-makers, you'll likely be asked to explain these ratios throughout your professional life. That's why it's very important to integrate and understand them.

Functional balance sheet uses and resources

The concepts of working capital and working capital requirements are closely linked to the understanding of the balance sheet, and more specifically to the concept of equity of what is called the functional assessment of a company.

THE functional assessment is a rereading of the classic accounting balance sheet, but we will return in detail to the precise definition of a functional balance sheet, and to the difference with an accounting balance sheet.

Do you have a business and want to regain control of your margins and your business model? Discover my solution Ultimate Business Dashboard which transforms your raw accounting data into performance indicators and a monthly dashboard.

Difference between accounting balance sheet and functional balance sheet

🧾 1. The balance sheet

- Established according to accounting standards (PCG in France),

- Classified by increasing liquidity on the assets side, and increasing liability on the liabilities side,

- Mainly used for general accounting, profit and loss preparation, and tax/legal obligations.

📊 2. The functional assessment

- Economic and financial representation of the company;

- Positions are reclassified according to their function in the operating cycle: investment, operation, financing;

- Allows an analysis of the financial structure, autonomy and balance of the company.

How to move from an accounting balance sheet to a functional balance sheet

To simplify as much as possible, the transition from the accounting balance sheet to the functional balance sheet is done by reclassifying the balance sheet assets, mainly with:

- The asset, which is generally called "Uses", and which includes:

- fixed assets which is generally renamed «"Stable jobs"» ;

- "Circulating operating jobs"« or "Operating current assets" which mainly include inventory and accounts receivable; ;

- the "non-operating current assets", which mainly consist of non-operating receivables; ;

- there active treasury (cash, cash on hand, marketable securities, etc.); ;

- The liabilities, which are generally called "Resources", and which include:

- THE share capital and the long-term financial debts which are classified as "Stable Resources"; ;

- THE current operating liabilities which includes supplier debts, tax and social security debts (excluding profit tax), deferred revenue; ;

- non-operating current liabilities, which include non-operating short-term financial debts and non-operating deferred revenues; ;

- there passive treasury (overdrafts, current bank loans, other short-term financing).

In the functional balance sheet, we therefore have the jobs (which correspond to the assets of the balance sheet) and the resources (balance sheet liabilities). To better understand what working capital is, it is important to remember that there is a equity between assets and liabilities, and that liabilities finance assets (so in functional balance sheet language, resources finance jobs).

We had seen this in the previous chapter, but it is always good to remember it at this level of learning. In practice, this principle of liabilities financing assets is materialized by the reason for existence of a company and the way in which it operates from a financial point of view.

Indeed, a company aims to generate profits, and to do this, she will use capital (money made available by partners for example) which can be found in liabilities and which are resources to finance equipment, employees, patents, etc. that we find in the assets and which are therefore jobs.

The aim of the job launch is to generate profit, which we will then place in the liabilities, in equity, in the form of net result, and which will ultimately be paid out as dividends to shareholders, or returned to the company.

So there is a sort of infinite cycle of money circulating within the company, which will bring us to the notions of working capital and the need for working capital. But before getting into the heart of the matter, we will first learn to classify the accounts according to whether they relate to the operating cycle (i.e. everything that circulates in the short term within the company as part of its current activity) or the long term (i.e. the lasting elements linked to investments, stable financing and the structure of the company).

Liabilities: short-term and long-term resources on the balance sheet

In the liabilities section of the balance sheet, two types of resources are distinguished. On the one hand, the share capital, brought by the partners of a company, and on the other hand, the debts, which are mainly credits granted by banks, but also supplier debts for example.

Regarding the distinction between share capital and debt through credit, many entrepreneurs talk about development through fundraising (therefore by bringing shareholders into the company, therefore into the share capital) or through debt (via a credit institution which will therefore have to be repaid, with interest).

When a business leader wants to borrow in order to finance its development and take advantage of what is called leverage (a concept that we will discuss in the next contents of the guide), the bank will analyze the company's ability to repay its debts (solvency). This financial analysis can lead to rejections, and the reasons are often misunderstood by entrepreneurs. This is precisely the purpose of this guide, which aims to popularize corporate finance and provide answers and potentially solutions to this type of problem.

To return to the passive, we therefore distinguish share capital, which constitutes a long-term resource provided by the partners, and debts, which decompose both in long-term resources and in short-term resources. They include:

- stable resources or long-term resources or permanent capital, such as medium or long-term bank loans;

- or unstable resources or short-term resources, such as supplier debts, tax and social security debts, or cash flow facilities (such as bank overdrafts).

Short-term resources are what we call current liabilities (suppliers, social security contributions, VAT due, cash flow liabilities, etc.). These are inherently unstable or short-term because they are not intended to be long-term, unlike share capital or bank loans, for example. Accounts payable, for instance, are orders placed with suppliers that need to be paid relatively quickly. Cash flow liabilities (such as bank overdrafts) are a form of bank borrowing that is not intended to be long-term.

It is therefore essential at this stage to understand that there is On one hand, there is the share capital and a portion of the financial debts, which constitute the so-called stable resources., And On the other hand, primarily supplier debts, as well as tax and social security debts, and also short-term financial debts, constitute unstable resources.It is precisely this distinction that will allow us to calculate and understand what we call working capital.

Stable and unstable jobs in the functional balance sheet

Then, in the functional balance sheet, the asset is designated as we said a little earlier by what we call "uses", which bring together what the company does with its resources, what it invests in. In other words, jobs refer to what the company does with its money.

Just as was the case with the Liabilities, we distinguish two main categories of employment on the Assets side:

✅ Stable jobs (or fixed assets): these are sustainable investments, intended to remain in the company for several years. These include, for example:

- The business fund

- Machines, equipment, vehicles

- Patents, software, buildings…

🔁 Unstable jobs (or current assets): these are elements to short cycle, which change regularly:

- The stock of goods or raw materials

- Available cash (in bank or cash register)

- Accounts receivable (what customers owe the company)

Let's start again the example taken from the last exercise of the previous course on the accounting balance sheet to understand the distinction between stable and unstable:

| FUNCTIONAL ASSESSMENT – Basic Structure | |

|---|---|

| ACTIVE | PASSIVE |

| Fixed assets • Business assets: 10 000 € • Machine : 5 000 € |

Permanent capital • Share capital: 10 000 € • Bank loan (long term): 5 000 € |

| Current operating assets • Goods (stock): 4 000 € |

Operating liabilities • Supplier debt: 3 000 € |

| Active treasury • Bank balance: 3 000 € (VMP, cash register…) |

Passive treasury (Overdrafts, short-term loans…) |

| Total Assets = 22 000 € | Total Liabilities = 22 000 € |

Structure of the functional assessment:

- Blue → Jobs and resources stable (long term)

- YELLOW → Cycle operating (Working Capital Requirement)

- Green → Active treasury (available cash)

- Red → Passive treasury (short-term financial debts)

Coming soon: calculation of working capital, net working capital requirement and net cash flow.

Now that we have grasped the subtle distinction between stable and unstable resources, and stable and unstable uses, we can define what working capital is.

Working capital (WC): what is it?

Before going further and popularizing what working capital can mean, let us first review the generic definition and the method of calculation:

Working capital (WC) is the difference between stable resources (also called permanent capital) and stable jobs (or fixed assets).

Working capital = Stable resources – Stable jobs

But what does the figure resulting from this calculation represent? How does the difference between stable resources and stable jobs provide us with information about a company's financial health?

In fact, the result of this difference (Stable Resources – Stable Jobs) corresponds to a financial safety margin, which I will dissect in a very progressive way so that the concept is well understood:

- The FR is a value (which we hope is positive) and which is the available surplus of long-term resources (share capital, reserves, long-term loans, etc.) once sustainable investments are financed (machinery, business assets, premises, etc.);

- So far, we understand that this is the difference between stable resources (passive) and stable jobs (on the asset side). Since stable resources finance stable jobs, the remaining difference (which we hope is positive) is therefore a financial surplus.

- This financial safety margin – which we call working capital – then allows the company to finance part of the current assets (the famous unstable jobs), such as stocks, accounts receivable, or cash, all or part of which is already financed by current liabilities.

- Regarding this current asset: when a company purchases goods, or awaits payments from customers, the amounts related to these transactions are included in current assets, and these amounts represent a funding need (to purchase goods or to bridge the gap while awaiting payment from a customer).

- However, this Current assets are normally already partly financed by current liabilities. (the famous short-term debts, typically supplier debts). Indeed, if for example we buy goods, we generally have a supplier lead time which allows us to have these goods. Well this supplier lead time will allow us to finance this purchase in a way, the time it takes for the company to resell these goods to the end customer, making a capital gain if possible.

- However, in practice, current liabilities (mainly supplier debts) does not allow the current assets to be fully financed, especially if the company buys a lot of goods, and takes a long time to resell them (to take a very simple example).

- As current liabilities are not sufficient to finance all current assets, It is precisely the Working Capital Fund (which we hope will be sufficient) which will cover the remainder to be financed.

So to summarize, unstable resources on the liabilities side of the balance sheet (such as supplier debts in particular, which are essentially short-term debts) are already supposed to finance all or part of the precarious jobs. But as this is generally not enough, especially when the company has a growing activity or is very active, We rely on working capital (which corresponds to stable resources less fixed assets, therefore the "stable resources always available" in a way) to compensate for the "remaining amount to be financed".«, And this “remainder to be financed” is precisely the Working Capital Requirement, which brings us to the next point.

Working capital requirement (WCR)

The working capital requirement (WCR) is calculated as follows:

Working capital requirement (WCR) = Current assets – Current liabilities (excluding short-term financial debt)

It represents the amount the company needs to finance its current assets (unstable uses), less current resources, and excluding short-term financial debts.

Indeed, we said just before that unstable resources are generally not sufficient to finance unstable jobs. And this "lack" is materialized precisely by the Working Capital Requirement, therefore the money that is lacking to finance unstable jobs, and that the Working Capital (what remains of the long-term resources once they have covered stable jobs) will finance.

In other words, a healthy company should ideally have working capital ≥ WCR, to be able to finance this WCR, quite simply.

And finally, what will remain when the working capital has finished financing the working capital requirement, will simply be “extra” money, which can then constitute what we call the net cash flow.

Current liabilities include all debts to be repaid within one year (or less than one year):

- Operating liabilities (related to the operating cycle) included in the calculation:

- Suppliers

- Expenses to be paid (salaries, taxes, social security contributions)

- Other operating liabilities

- Short-term financial debts (excluded from the calculation):

- Bank loans with a term of less than one year

- Bank overdrafts

- Short-term share of long-term debt

In traditional accounting, all these debts appear under current liabilities. However, The calculation of working capital excludes short-term financial debt, because we are only interested here in debts related to operations, not external financing.

Short-term financial debts are external resources, therefore they do not reduce the need for operational financing.

That's why the working capital requirement (WCR) formula becomes:

Working capital requirement (WCR) = Current assets − Operating current liabilities

With Operating current liabilities = Current liabilities – Short-term financial liabilities

In summary:

- Current liabilities (accounting) = Operating liabilities + Short-term financial liabilities

- Current liabilities used for working capital requirements in the functional balance sheet = Only operating liabilities (excluding short-term financial liabilities)

Link between FR, WCR and Net cash flow

Working capital (WC) and net working capital requirement (NWC) are directly linked to cash flow. Indeed, on the one hand, WC measures the surplus of stable resources after these have financed stable uses, and NWC measures the need for this surplus in order to finance operating activity, once current liabilities less short-term financial debts have been deducted from current assets.

From this, we can logically deduce that if the working capital (FR) finances the entire working capital requirement (BFR), and there is still an amount available, this amount simply corresponds to the net cash position:

Cash = FR – BFR

Cash assets, cash liabilities, and net cash

In the functional assessment, the active treasury groups immediately available cash (bank balances, easily convertible securities, cash), while the passive treasury includes the short-term financial resources used to meet a cash flow need (bank overdrafts, (loans of less than one year, current bank overdraft facilities, short-term portion of long-term loans).

Net cash flow is the balance between these two items:

Net cash = Cash assets − Cash liabilities.

It therefore represents the company's actual liquidity after taking into account its immediate financial commitments.

Mathematically, it is also equal to FR − BFR, which guarantees the balance of the functional balance.

So :

- If working capital > working capital requirement → positive net cash flow (excess liquidity)

- If working capital < working capital requirement → negative net cash flow (deficit, often covered by cash liabilities)

- If FR = WCR → zero net cash flow

So ultimately, the question is if the FR is greater than the BFR (which is rather a good thing), or if it is less than the working capital requirement, which will probably require external financing (and we will see this case in the diagrams below).

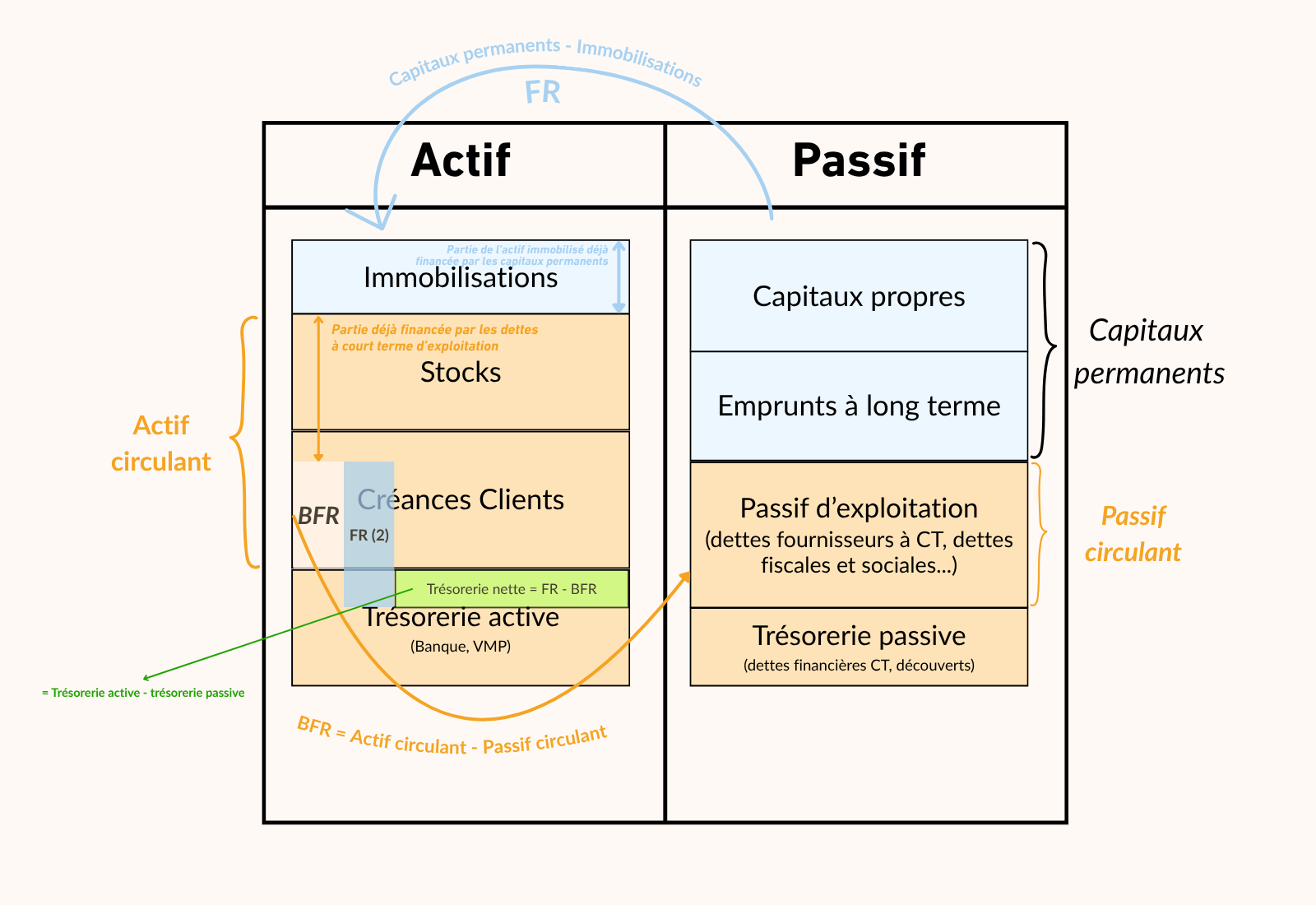

Diagram of a balance sheet with positive working capital exceeding working capital requirements.

Take the time to watch and rewatch the video I made below, in order to master this intellectual gymnastics relating to the functional balance sheet, and the concepts of FR, WCR and Net Cash.

Be aware that the size of the blocks is very important in balancing the balance sheet, and in understanding the balance sheet masses of a functional balance sheet.

To help you digest all of this, here's how we can break down the video:

- part of unstable employment is covered by short-term debts (such as supplier debts for example);

- what remains constitutes the Working Capital Requirement;

- Working capital, which is the result of stable resources minus stable uses, is represented by the blue block., which, as we can see, is higher than the working capital requirement (WCR). ;

- therefore, The working capital requirement is well financed by the operating income., or in other words, FR supports BFR, he compensates him financially; ;

- Furthermore, since FR > BFR, this working capital is sufficiently high to generate additional cash, which therefore logically corresponds to the difference between FR and BFR; ;

- You will notice that the balance sheets are well balanced, with a FR that is equal to the WCR + net cash, and assets and liabilities that are equal.

And here is the final diagram in frozen image:

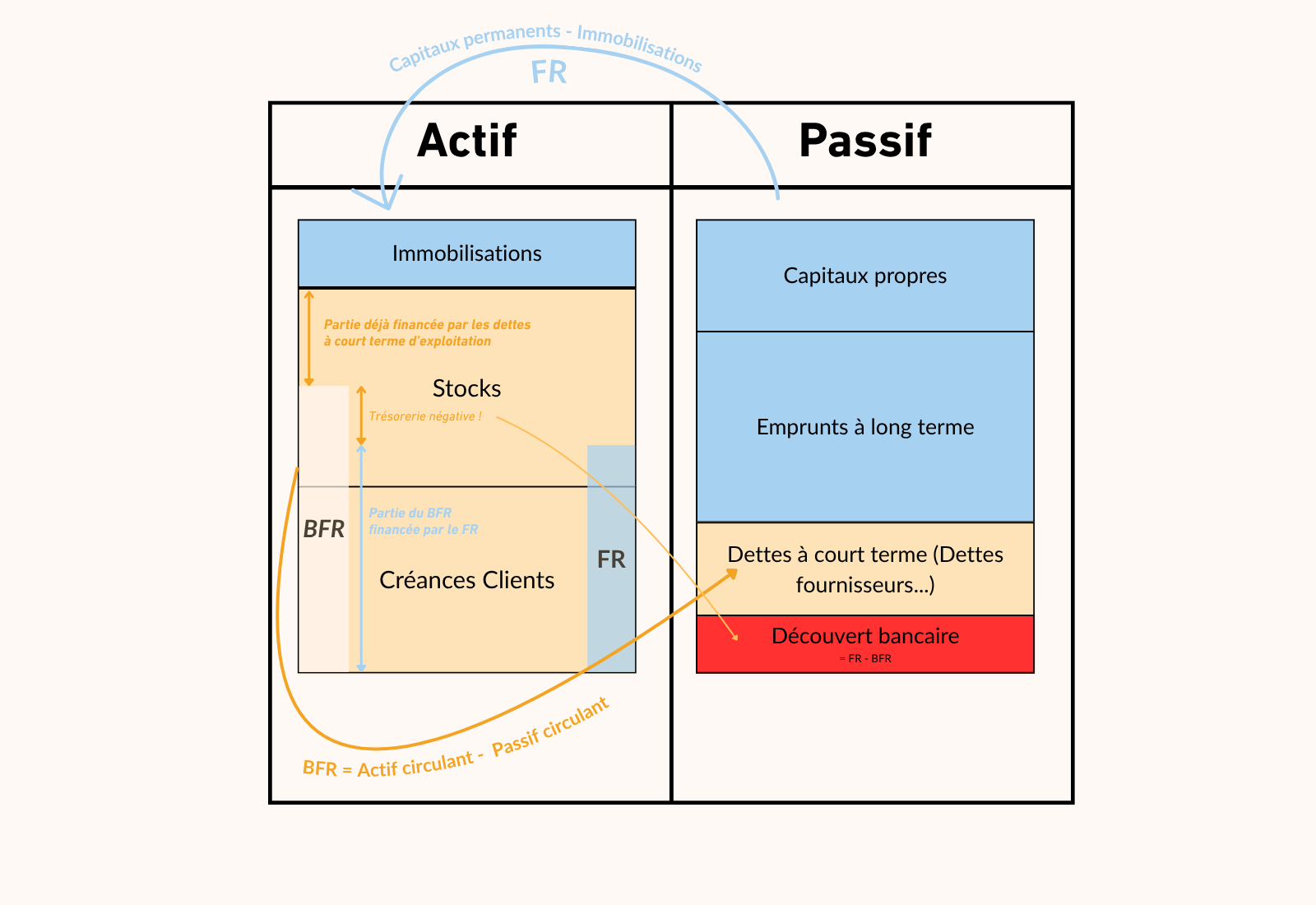

Diagram of a balance sheet with positive working capital but with working capital < working capital requirement

In the diagram above, we can see the case of a balance sheet where the working capital is indeed positive, but it is not sufficient to cover the company's operating cycle (current assets):

- The company has substantially increased its stocks of raw materials or goods, perhaps in anticipation of increased demand or supply disruptions.;

- THE The amount of customer receivables has also increased, a sign of longer payment times from customers; ;

- On the other hand, the supplier debts have not increased proportionally, so the company may have been forced to "settle too early" in a way with its suppliers; ;

- Result: le FR is less than BFR, therefore iIt is not sufficient to cover the company's operating cycle., which theoretically results in a negative cash flow, hence the bank overdraft on the liabilities side in order to balance the balance sheet.

- The company is therefore experiencing cash flow pressure.

This case could be interpreted as poorly anticipated growth of the company. It made significant purchases of raw materials or goods, or it grew too quickly, without compensating for this increase in activity by:

- a negotiation of longer supplier deadlines,

- an acceleration of customer collections,

- tighter inventory management,

- or external financing, through bank credit or capital increase (long-term debts).

Of course, this reading remains purely theoretical, but it illustrates a common case among many impatient entrepreneurs: the uncontrolled growth and unfunded, which can lead to cash flow difficulties even though business is progressing, which is unfortunate. And this can lead to bankruptcy if the company suddenly has to deal with an unforeseen setback.

Understanding these mechanisms helps leaders and managers anticipate these tensions, manage operational cycles more calmly, and at the very least act consciously when taking risks. This is the whole point of this guide, which I hope will help many.

Cash flow assets and liabilities

In the first diagram, I chose to represent both active cash and passive cash in order to show their distinct position in the functional balance sheet — it is quite possible to have both simultaneously, as active cash reflects available liquidity while passive cash groups together short-term financial liabilities.

In the second diagram, to simplify the reading of the FR < BFR case, I merged these two items into a negative net cash position, materialized by a bank overdraft (passive cash), which compensates for the financing deficit.

That being said, even in the second case (with working capital < working capital requirement), it is entirely possible to have both active cash (e.g., bank balance) and passive cash (e.g., overdraft). In my diagram, I simplified things by only showing the bank overdraft to illustrate negative net cash, but in reality, the company can have liquid assets while also being overdrawn.

Indeed, a company can have cash on hand (active cash) while also being overdrawn (passive cash), because these balances can originate from different bank accounts or from optimized cash flow management. Ultimately, net cash remains the overall balance: Active Cash − Passive Cash.

What happens in the case of a negative FR?

Working capital is often positive, and the challenge lies in financing all or part of the working capital requirement. However, there may be cases where working capital is negative, which immediately signals a major risk for the company, as it means that stable resources are insufficient to cover stable uses of funds.

- Positive working capital → permanent capital finances more than fixed assets → surplus available to finance the operating cycle.

- Negative working capital → permanent capital is insufficient to finance fixed assets → the company needs to resort to short-term financing to finance fixed assets (overdrafts, cash credits, suppliers, etc.), which is very risky.

A negative working capital indicates financial fragility, as the company is heavily reliant on short-term financing, which is not only expensive but also not necessarily sustainable. This can rarely occur temporarily.

- for hyper-growth companies facing costly investments financed by upcoming fundraising rounds; ;

- if the working capital requirement is also negative (so the need to finance stable jobs is somehow "offset" by a negative working capital requirement, i.e. by very short customer payment terms before having to pay suppliers, and little stock to finance, which generates positive cash flow); ;

- or in consulting firms for example, where working capital is low (customer payments and no stock) and working capital is also low because of few investments.

| Case | FR | BFR | Treasury | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive FR + Moderate BFR | + | + | + | Ideal |

| Positive FR + high BFR | + | ++ | − | Operational problem |

| Negative FR + very negative BFR | − | −− | + | Rare, fragile, temporary |

| Negative FR + positive BFR | − | + | −− | Very dangerous |

A negative working capital requirement (WCR) is never ideal, but exceptionally viable temporarily if the working capital requirement (WCR) is significantly negative. Otherwise, it's a major warning sign.

Link between working capital, working capital requirement, and customer and supplier payment terms

As you can see, these concepts of Working Capital and Working Capital Requirement are linked to whether or not a company's activity increases, but also to the payment terms granted to customers, and the payment terms granted by suppliers.

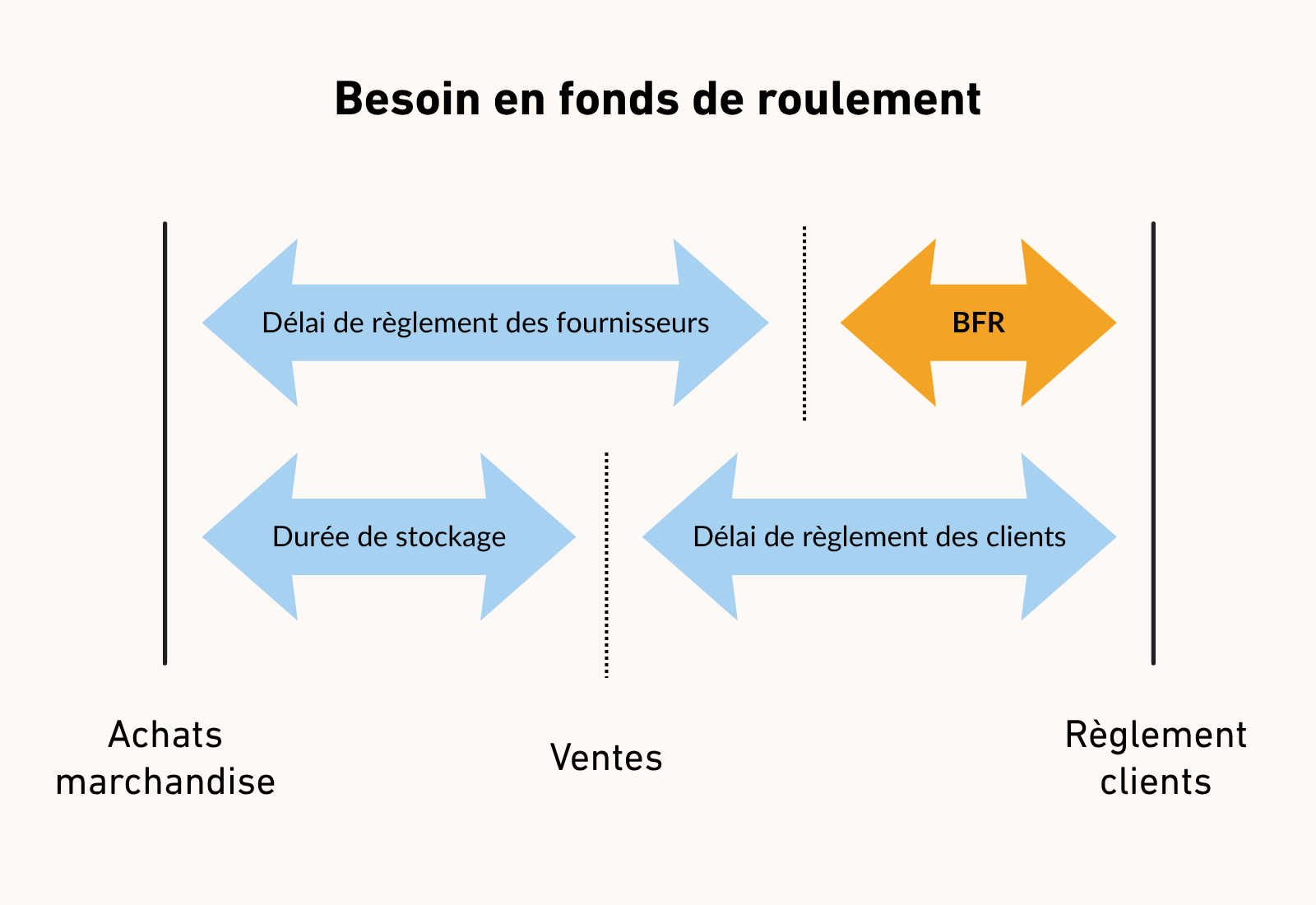

Depending on these payment terms, the company will be more or less exposed to cash flow pressure and a higher or lower working capital requirement. This topic will be addressed in the following chapters, which focus in particular on business forecasting and supplier payment terms, but to provide some initial clarity, here is a diagram illustrating this issue of payment terms:

To make things clearer, we will illustrate these concepts of FR, BFR and Net Cash Flow with simple and practical examples.

Example 1 of calculating FR, BFR and Net Cash Flow

Let's take the same case from the previous course on the balance sheet to better understand these concepts of working capital and working capital requirement:

| ACTIVE | PASSIVE |

|---|---|

| Machine: €5,000 | Share capital: €10,000 |

| Deposit paid: €1,000 | Bank loan: €5,000 |

| Stock of materials: €2,000 | Supplier debt: €1,000 |

| Trade receivables: €3,000 | |

| Bank: €5,000 |

Legend :

- Stable jobs

- Unstable jobs

- Stable resources

- Unstable resources

From this balance sheet, try to calculate:

- The FR

- The BFR

- And the Net Cash.

And compare with the results below.

Detailed calculations from this balance sheet:

- Stable resources (Share capital + Bank loan) = €10,000 + €5,000 = 15 000 €

- Stable jobs (Machine + Deposit paid) = €5,000 + €1,000 = 6 000 €

- ➡ Working capital (FR) = €15,000 – €6,000 = 9 000 €

- Unstable jobs (Stocks + Accounts receivable) = €2,000 + €3,000 = 5 000 €

- Unstable resources (Supplier debt) = €1,000

- ➡ Working capital requirement (WCR) = €5,000 – €1,000 = 4 000 €

- ➡ Net cash flow = FR – BFR = €9,000 – €4,000 = 5 000 €

This net cash of €5,000 corresponds to the amount shown in the bank assets. This confirms that:

- The company generates positive working capital (it has a surplus of long-term resources),

- This FR covers its working capital requirement,

- It therefore generates positive net cash flow, a sign of good financial health.

Example 2 of calculating FR, BFR and Net Cash Flow

Here we have a working capital balance sheet from which we calculated the FR and the BFR, but a subtlety has crept into this example.

| FUNCTIONAL ASSESSMENT | |

|---|---|

| ACTIVE | PASSIVE |

| Stable jobs (Fixed assets) • Business assets: 10 000 € • Machine : 5 000 € Total fixed assets: €15,000 |

Stable resources (Permanent capital) • Share capital: 10 000 € • Bank loan (long term): 5 000 € Total permanent capital: €15,000 |

| Working capital (WC) = €15,000 − €15,000 = 0 € | |

| Current operating assets • Goods (stock): 4 000 € (Customer receivables: €0) |

Current operating liabilities • Supplier debt: 3 000 € (Tax/social security debts: €0) |

| Working capital requirement (WCR) = (€4,000) − (€3,000) = 1 000 € |

|

| Active treasury • Bank balance: 3 000 € (VMP: €0) |

Passive treasury (Discoveries: €0) (CT loans: €0) |

| Net cash flow = Cash assets − Cash liabilities = €3,000 − €0 = +3 000 €Verification: FR − BFR = €0 − €1,000 = -€1,000 ? → Inconsistency detected! |

|

| Total Assets = 22 000 € | Total Liabilities = 22 000 € |

Warning: Inconsistency detected!

FR = €0, BFR = €1,000 → FR − BFR = −€1,000

But net cash = +€3,000 → Difference of €4,000

Explanation : The bank balance (€3,000) finances in reality the working capital requirement (€1,000) And covers the absence of FR. This means that the company is living off its current cash reserves, which is risky in the long term.

Ideal solution: Increase working capital (e.g., capital contribution or long-term loan) to finance working capital requirements without depleting cash reserves.

As you have seen, in this example, net cash is not equal to the difference between working capital and net working capital, because it is masked by active cash, hence the importance of understanding all the concepts mentioned here in order to anticipate all scenarios.

Now that we understand how the functional balance sheet is constructed, and how Working Capital (WC) and Working Capital Requirement (WCR) interact, the question we can ask ourselves is how this can be useful to us in practice, beyond the theory. To illustrate this, let's take the example of a seasonal business.

Some companies, particularly in sectors with strong seasonality (tourism, summer catering, ice cream sales, equipment rental, etc.), see their BFR fluctuates strongly depending on the time of year. These variations have a direct impact on cash flow and must be anticipated to avoid temporary financial tensions.

Understanding the effect of seasonality on working capital requirements

Let's imagine a company that generates the majority of its revenue during the summer. The graph below illustrates the evolution of working capital throughout the year:

- Working Capital (WC) is generally stable; it represents, as a reminder, the company's long-term resources available to finance its stable jobs as well as its operating cycle.

- BFR varies over time depending on activity.

- Net cash results from the difference between the FR and the WCR.

Why does the BFR increase during the high season?

In summer, although the company sells a lot, It also incurs a lot of expenses to support this activity :

- Building up large stocks

- Possible advance payment of certain suppliers

- Seasonal recruitment and salaries

- Payment deadlines sometimes granted to customers (BtoB, agencies, etc.)

💡 So, even if revenue is high, the money hasn't been fully collected yet, while a large portion of the expenses have already been paid out. This creates a significant need for working capital, and can lead to cash flow pressures.

This may seem completely counterintuitive to a novice or an entrepreneur unfamiliar with corporate finance, and yet an increase in activity can very often create cash flow tension that sometimes leads to questioning on the part of the entrepreneur, caught between his theoretical economic model and the reality on the ground.

Why does the BFR decrease in winter?

In low season:

- There is no more commercial activity, so no new stock or staff to finance.

- Customers were cashed out during or shortly after the summer.

- Suppliers have been paid, there are no more supplier debts.

- Result: the operating cycle is at a standstill, the WCR falls.

Sometimes the WCR can even become negative, which means that the company has unused cash.

Now that we've said that, what can we do to optimize all of this?

Management objective: smooth the WCR over time

One possible objective of a manager could be to try to bring the WCR back to the "center", that is to say to reduce seasonal fluctuations, because this would allow:

- To avoid cash flow tensions in summer.

- To make better use of the money available in winter.

How to stabilize the WCR?

Here are some levers:

- Negotiate longer payment terms with suppliers after the peak period.

- Reduce customer payment times (by installments, immediate invoicing, etc.)

- Optimize stocks to avoid overstocking.

- Look for a complementary activity out of season (related products/services, off-season rental, diversification, etc.).

Conclusion on BFR variations

A high WCR is not necessarily a sign of poor management, but it should be anticipated, especially in cases of strong seasonality. By controlling cash flow gaps, the company can avoid systematic recourse to short-term debt or bank overdrafts, and thus secure its financial stability.

The Management Working Capital

We know that the working capital requirement of the balance sheet can be calculated from the functional balance sheet according to the following formula:

BFR = Current Jobs – Current Resources

This approach provides a snapshot at a given time, generally at the end of the financial year, for example, on December 31. It allows the company's financial structure to be analyzed based on the balance sheet balances. It is therefore a "static" WCR, so to speak, and is true at the time the balance sheet is closed.

In pure management, we can calculate a management WCR, which is an annual average, using a more operational formula:

WCR = Average outstanding customer receivables + Average stocks – Average outstanding supplier debts

This second formula is based on averages over a period (for example, over the year), which provides a more dynamic view of the working capital requirement, useful for cash flow management. It reflects the average immobilization of cash in the operating cycle, and is more representative of the actual financing requirement over the year.

The two approaches are consistent but should not be confused: the first is structural, it is a snapshot taken at a given moment of the working capital requirement, while the second is functional and forecasting, it is a realistic average of the requirement.

🎯 Concrete example:

Let’s imagine a seasonal business (summer catering for example):

- On December 31 (balance sheet), stocks are low, as are customer receivables, and therefore the WCR is low or zero.

- But in reality, during the summer, this caterer had to finance a large stock, grant customer deadlines, and therefore had a high WCR in June-July.

The annual average of these items (stocks + receivables – payables) shows a much greater cash requirement than the year-end balance sheet suggests!

But then how do we calculate average stocks, average outstanding customer receivables, and average outstanding supplier debts?

Calculation of average inventories, average customer receivables and average supplier payables

When calculating the WCR from management data (and not from the functional balance sheet), we need average outstanding amounts, i.e. averages over the year.

However, financial statements (the balance sheet) only provide values at a given time, generally December 31.

To obtain the annual averages, we proceed as follows:

Average stock = (Stock as of 12/31/N-1 + Stock as of 12/31/N) ÷ 2

→ “Stocks and work in progress” line of the balance sheet.

Average customer receivables = (Receivables as of 12/31/N-1 + Receivables as of 12/31/N) ÷ 2

→ “Customers and related accounts” line of the balance sheet.

Average supplier debts = (Debts as of 12/31/N-1 + Debts as of 12/31/N) ÷ 2

→ “Suppliers and related accounts” line of the balance sheet.

These averages make it possible to reason over the entire year to analyze more precisely the functioning of the WCR, particularly in relation to the actual activity of the company.

These values are useful for modeling the real cash requirement and not just the accounting requirement.

With these three data, we can thus reconstruct the formula for management working capital:

WCR = Average stocks + Average customer receivables – Average supplier payables

When the WCR calculation gives a negative result, it means that the company has a surplus of short-term resources compared to its operating needs. In other words, operating liabilities (particularly trade payables) are greater than current assets (inventories and trade receivables).

In this case, the WCR is said to represent a resource for the company, sometimes called working capital. This situation is particularly common in large-scale distribution, fast food, or certain service activities with low storage requirements.

Why? Because in these sectors:

- Customers pay immediately, often in cash (card, cash, etc.).

- Suppliers are paid with a delay, sometimes 30 to 60 days.

Result: the company quickly collects its sales, without tying up too much cash in inventory or receivables, and temporarily has excess cash thanks to supplier payment delays.

➡️ This type of business model is very favorable to cash flow, because the activity itself generates cash even before the company has paid all its operating expenses.

⚠️ Caution: a negative WCR can mask structural weaknesses

A negative WCR may give the illusion of excellent financial health, as it generates significant free cash flow, especially during periods of high activity. However, this does not guarantee the long-term soundness of the business model.

Let's take the example of fast food or certain retail businesses:

Cash flow can be very positive, especially from cash payments from customers.

However, behind this apparent performance, margins may be low, fixed costs high, and dependence on attendance or seasonality very strong.

➡️ The income statement is then essential to go further, because it provides information on the real profitability of the activity: gross margin, operating expenses, net profit, etc. In other words, it is not because the cash flow is comfortable that the model is profitable or viable.

Furthermore, some negative WCR may stem from very long supplier lead times, which artificially improve cash flow. This means that the company is shifting the financing burden onto its suppliers, which can be risky if they end up demanding faster payments, or if it harms the business relationship. This type of strategy can distort the WCR analysis and mask imbalances.

➡️ In summary, a negative WCR is a natural financing opportunity, but it should never be analyzed in isolation. It is essential to cross-reference it with other financial indicators, such as those in the income statement, to assess the robustness of the business model.

WCR in days of turnover

It is also possible to calculate the WCR in days of turnover using the following formula:

WCR (in days of turnover) = [ WCR / Annual turnover excluding tax ] * 365

🔎 This is like asking: "How many days of sales are needed to cover the working capital requirement?"

📌 What is it for?

Expressed in number of days, the WCR becomes:

- more readable for the manager or financiers;

- year-on-year comparison;

- comparison between companies in the same sector, regardless of their size.

👉 For example:

- A 30-day working capital requirement means that the company must finance the equivalent of 30 days of activity for its operating cycle.

- A WCR of -10 days means that the operating cycle generates cash, the company does not need to finance its activity over these 10 days.

✅ Example of WCR in number of days

A company has an annual turnover of €400,000 and a working capital requirement of €100,000.

WCR in days = (100,000 / 400,000) × 365 = 92.25 days

The company therefore needs to finance 3 months of activity (its working capital requirement of 92 days) to run its operations.

📈 Management ratios linked to WCR

You will have understood through this course that the notion of WCR is directly linked to 3 types of deadlines relating to the operation of the company:

- stock turnover time: how many days stocks remain in the warehouse,

- the timeframe for customer receivables: how long does it take the company to collect its receivables,

- the supplier debt period: in how many days it pays its suppliers.

These three elements directly condition the level of the WCR, and the whole challenge for the company will consist of playing with these three deadlines according to the commercial activity, which is similar to management.

🧮 1. Average inventory turnover time

Average stock / Purchase cost of goods or materials consumed × 365

With Average stock = (initial stock + ending stock) / 2

You understand very simply the calculation of the average stock, which is neither more nor less than a simple average calculation between the stock recorded at the beginning of a given financial year or period, and the stock recorded at the end. We thus have a value which represents the average of current assets stored in the company over an accounting year. Then:

- We divide this average stock by the purchase cost of the goods or raw materials consumed over the year. This gives us a proportion ratio, that is to say: "What share of our annual consumption remains immobilized on average in stocks, compared to what we bought or consumed during the year?"

- This ratio is multiplied by 365 days, in order to express this proportion in number of days of average storage.

This average inventory turnover ratio measures the average time items remain in the company's inventory, in days. The longer this time, the higher the working capital requirement. The lower it is, the faster the company turns over its inventory, which is often good for cash flow and flexibility.

👉 Optimized inventory management (just-in-time supply, intelligent destocking, etc.) helps reduce this ratio and therefore the WCR.

📌 Simple example of average inventory turnover time

- Initial stock: €20,000

- Final stock: €30,000

- Cost of purchasing goods consumed during the year: €180,000

➡️ Average stock = (20,000 + 30,000) / 2 = €25,000

➡️ Average turnaround time = (25,000 × 365) / 180,000 ≈ 50.7 days

✅ This means that, on average, an item remains in stock for 51 days before being used or sold.

What is the difference between goods and raw materials?

The difference between the cost of goods purchased and the cost of materials consumed depends on the type of business activity. Here's how to distinguish between them and know which one to use in each case:

🔹 1. Cost of purchasing goods

This term is used for a commercial company, that is to say, one which resells products which it buys without transforming them.

- Examples: supermarket, clothing store, e-commerce site, bookstore, etc.

- What the company buys = goods

- What she resells = these same goods

👉 In this case, we are talking about merchandise inventory, and we use the Cost of Goods Sold.

🔹 2. Cost of purchasing raw materials consumed

This term is used for an industrial company, that is, one that transforms raw materials to create a finished product.

- Examples: bakery, carpentry, manufacturing plant, etc.

- What the company buys = raw materials

- What she resells = products made from these materials

👉 In this case, we talk about raw material stock, and we use the purchase (or production) cost of the materials consumed

⚠️ Sometimes a business can do both (e.g., a caterer that sells homemade and pre-prepared products). In this case, you can:

- separate the two types of stock and consumption to make two different ratios,

- or make a global ratio, but it will be less precise.

🧾 2. Average customer payment time

This ratio measures the average payment period granted to customers. The longer it is, the more cash the company must advance, which increases the working capital requirement.

Average customer receivables × 365 / Turnover including tax

With : Average accounts receivable = (Accounts receivable at the start of the financial year + Accounts receivable at the end of the financial year) / 2

This data is found in the balance sheet, under assets (often the line "Customers and related accounts" or "Customer receivables"). The start of the financial year corresponds to the balance sheet N-1, the end to that of year N.

👉 Reducing this delay through down payments, effective reminders, or strict payment terms can improve cash flow.

📦 3. Average payment period for suppliers

Average supplier debts × 365 / Purchases including tax

With : Average accounts payable = (Account payable at start of year + Account payable at end of year) / 2

This data is found on the liabilities side of the balance sheet, generally on the line "Trade payables and related accounts". The start of the financial year corresponds to the balance sheet N-1, the end to that of year N.

This ratio measures the average payment period granted by suppliers to the company. The longer it is, the more it reduces the working capital requirement.

👉 But be careful: stretching it too far can damage the supplier relationship or affect the company's reputation.

🔁 Operating cycle: the link with the WCR

By combining these three time periods, we can reconstruct the company's operating cycle:

Operating cycle = Average inventory turnover time + Average customer payment time – Average supplier payment time

This cycle, expressed in days, gives a dynamic reading of the WCR. The longer this cycle, the higher the WCR.

✅ Simplified example of calculating the operating cycle

- Average stock turnover time: 20 days

- Average customer payment period: 45 days

- Average supplier payment period: 40 days

Operating cycle = 20 + 45 – 40 = 25 days

The operating cycle is 25 days: this means that the company must finance an average of 25 days between disbursements (purchases, stocks, etc.) and customer collections.

The FR and the BFR in conclusion

Because repetition helps you better understand the concepts, here is a summary of Working Capital and Working Capital Requirement.

Working capital (WC) corresponds to the difference between the company's permanent capital (i.e. the company's long-term financial resources) and fixed assets (i.e. the company's long-term uses, i.e. the amounts that have been invested by the company using resources for everything concerning the company's long term).

This difference thus materializes the amount available from the long term but which can be used to finance the short-term activity of the company, which is also called current assets, and which corresponds to the operating cycle of the company (therefore the purchase of raw materials, storage, customer receivables, etc.).

Working capital requirements are a short-term concept, the opposite of working capital, since they represent the amount of cash needed to operate the business: they indicate the amount of money used by the company's stocks or by customer receivables, less supplier debts, and which is therefore not available.

🔎 Exercise 1: Understanding Imbalance

A company presents the following elements on its balance sheet:

- Stocks: €50,000

- Trade receivables: €70,000

- Supplier debts: €40,000

- Permanent capital: €100,000

- Fixed assets: €85,000

Answers:

1. The WCR increases because stocks increase and so do customer receivables (longer lead time).

2. If the FR does not change, net cash flow decreases: risk of liquidity tension.

3. Possible solutions:

– Finance part of the WCR with an overdraft or a line of credit

– Reduce customer delay or improve recovery

– Negotiate longer supplier lead times

🧠 Exercise 3: Analysis of a diagram

You observe a balance sheet diagram where:

- Fixed assets = €90,000

- Permanent capital = €100,000

- Inventories + Accounts receivable = €80,000

- Supplier debts = €30,000

- Bank overdraft liability: €10,000

Exercise 4: Qualitative analysis of seasonal WCR

1. Why might a seasonal business face cash flow pressure in summer, even if its turnover is very high at that time?

Correction:

Because even if the turnover is high, the money is not yet collected immediately (customer delays), while many expenses have already been incurred (inventory, seasonal salaries, suppliers). This generates a high WCR and cash flow pressure.

Exercise 5: Calculation of management working capital

2. Calculate the management working capital requirement from the following data:

- Stock as of 12/31/N-1: €40,000

- Stock as of 12/31/N: €60,000

- Trade receivables as of 12/31/N-1: €90,000

- Trade receivables as of 12/31/N: €110,000

- Supplier debts as of 12/31/N-1: €70,000

- Supplier debts as of 12/31/N: €50,000

Your answer:

Correction:

Average stock = (40,000 + 60,000) / 2 = €50,000

Average receivables = (90,000 + 110,000) / 2 = €100,000

Average debts = (70,000 + 50,000) / 2 = €60,000

WCR = 50,000 + 100,000 – 60,000 = €90,000

Exercise 6: WCR in days of turnover

3. A company has a working capital requirement of €75,000 and an annual turnover of €300,000. Calculate its working capital requirement expressed in number of days of turnover.

Correction:

WCR in days = (75,000 / 300,000) × 365 = 91.25 days

Exercise 7: Interpretation of a negative BFR

4. A fast food company has a working capital requirement of -€15,000. Is this necessarily good news? Why should we remain cautious?

Correction:

A negative WCR may be good news in the short term (immediate collection, suppliers paid late), but it can mask structural fragility: low margins, dependence on supplier deadlines, fragile economic model. It must be cross-referenced with profitability.

👉 Next chapter: leverage

📖 Back to Table of Contents