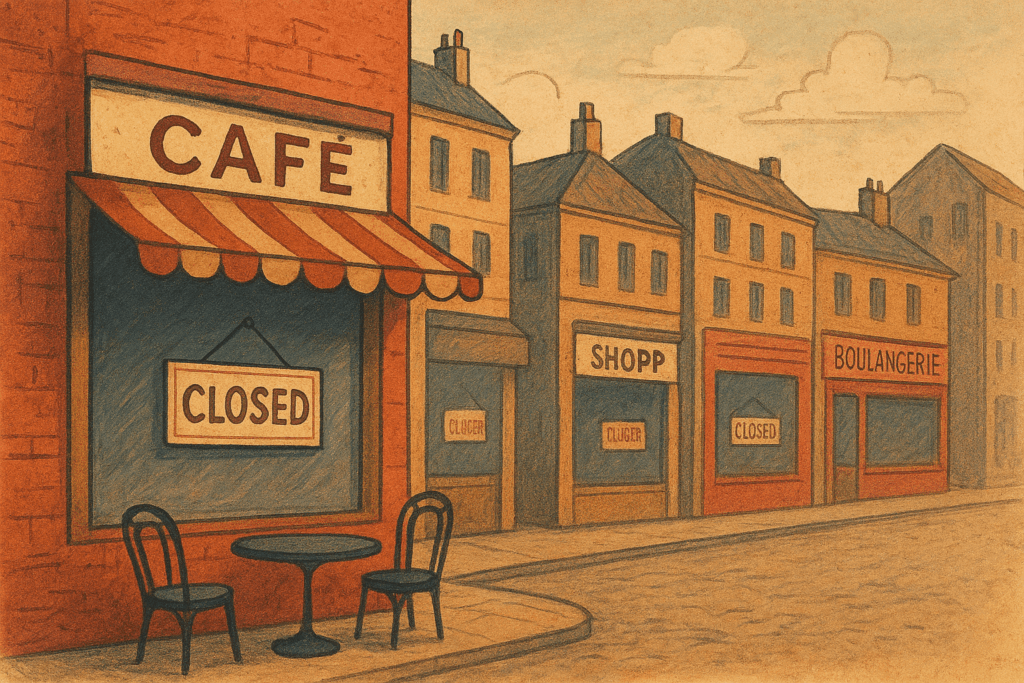

The image is appealing: setting up shop in the city center, opening a restaurant, a boutique, making a living from one's passion, being one's own boss — the promise of the dream.

But behind this dream often lies a harsh reality. In large cities, particularly in Paris, landlords—whether private investors or institutions—have made a habit of speculating on this dream, and one might wonder if, instead of selling the right to operate a business, they aren't simply selling a mirage. And in the end, it's often the tenant-business owner who pays the heaviest price.

Here's why.

The dreamer's irrational choice

When you want to make a living from your passion, to "open your own place," you don't always have the rational mind of a seasoned business owner. You choose based on gut feeling, you bet on the location, the right address, the "atmosphere," the "potential.".

We accept a high rent, we accept a difficult period, and we eventually accept exhaustion.

Since what I call the "World After" (post 2020), with successive crises (Covid-19, inflation, cost of energy, geopolitics, distrust of populations, loss of sovereignty, etc.), economic reality has caught up with many of those who believed in the dream.

The shopkeeper often finds himself without a salary, struggling with daily hardships, administrative problems, and frequently suffering from declining health. This downward spiral doesn't happen rapidly; on the contrary, it's gradual, which brings us to the next point.

The inertia effect

In a "rational" real estate market, prices are corrected when supply no longer works, rents are lowered when premises remain empty, supply is adapted to demand.

But in retail, and especially in city centers, we are seeing a phenomenon of’inertia combined with information asymmetry :

-

The landlord knows that the premises will remain occupied (even if only lightly), so he maintains a high rent — the risk is low for him.

-

The prospective business owner, often poorly equipped with geomarketing tools, unaware of the actual performance of a location, uninformed of the number of local failures, and blinded by his dream, agrees to take the rent as is.

-

The premises remain occupied, the balance is suboptimal: the shopkeeper survives, doesn't really make a profit, but pays rent. The landlord "makes his money" at the expense of the shopkeeper and his resilience.

- Even worse, the tenant cannot lower prices, even with the desire to "correct" the market and attract new customers, because the customers are simply no longer there, or consume less, and a price reduction would be a death sentence for the tenant, precisely because of unreasonably high fixed costs compared to market reality, including rent, energy costs, and social charges.

In short: the landlord is taking advantage of a blocked market, fragile information, and a merchant willing to take the risk of the dream.

The mirror to the larks

This is the crux of my argument: the landlord is no longer so much selling access to a customer base, a catchment area, or a thriving market (and even less so a secure commercial future). What they are actually selling is... a right to dream.

And this dream lasts until the merchant is exhausted — time, investment, health take a hit — and the landlord will find a new dreamer tenant.

The changes we are currently experiencing (digitalization, teleworking, crises, loss of purchasing power, insecurity in large cities, changes in consumer behavior) are all factors that weaken the promise of success in retail.

And yet, rents are still not falling, and landlords are in some ways primarily responsible for the cascade of bankruptcies, as they often represent the "unavoidable fixed cost" that the business owner cannot offset.

When the tenant gives up, the landlord eventually finds another tenant to take on.

4/ Result

The result is twofold:

-

For the tenant-business owner: sacrifice of their time (often much more than in a salaried job), their money (investment, fitting out, equipment, marketing…), their health (stress, expenses, uncertainty). Often, little or no return meets expectations.

- For cities: a fragile economic fabric, high turnover, premises that frequently change hands or even remain empty, neighborhoods struggling to regain stable momentum. The retail dream can turn into a wasteland of activity.

In other words: by maximizing their profit, landlords sacrifice two lives, the life of the shopkeeper, and the life of the neighborhood.

5/ The solution

What if we reversed the logic a little? Rather than considering every commercial space as a "profitable location to be squeezed out as much as possible", we could imagine more solidarity-based leases.

In order for the market to correct rental prices (difficult location, weak clientele, high turnover, insecurity), several solutions are possible, but these are only avenues for consideration:

-

The landlord points out that his income depends the tenant's success. If the tenant closes, the landlord also loses. Therefore, a landlord who supports (or at least doesn't sabotage) their tenant is acting in the common interest. And "CSR" landlords, who have a good public reputation and are rated transparently, would be another step towards a better society.

-

We could imagine tools for transparency: ratings/scores for rental properties (frequency of failures, average occupancy period, average revenue, etc.). This way, the tenant would be better informed before signing.

-

Finally, in line with the redistribution principles that France is so fond of, we must recognize that small business owners receive no support despite the multitude of constraints they face (inspections, taxes, insecurity, low pensions). Making their status more viable is good for the city center, for the social fabric, for the city as a whole.

In short: ensure that the commercial lease is not a trap for the dreamer, but a tool for success.

Conclusion

The dream of launching a restaurant, a concept store, or a shop in the city center is noble. But simply setting up shop isn't enough: you have to make it happen. And in many cases, it's the landlord who has rationalized their approach: they sell a dream, they collect rent, and then whatever happens, happens.

The merchant, however, assumes the risk and the human cost.

If we want to revive local commerce, we need to rethink the landlord-tenant relationship, create transparency, rebalance risks, and consider that commercial premises are an element of the urban fabric — not just an asset for a purely commercial landlord.

Because ultimately, it's human lives—those of the shopkeeper, their employees, and the local clientele—that give a business its true value. And a lease that makes sense should recognize that!